Offsetting your global footprint with solar storage systems and more in New York City

According to the EPA, organizations working to lower their greenhouse gas (GHG) emissions footprint have various mitigation options at their disposal, “including activities to reduce their direct emissions, indirect emissions like energy efficiency measures and switching to green power, and paying for external reductions. Knowing the differences between instruments like RECs and offsets is critical to deciding how both may be useful to your organization.”

Organizations track and report their GHG emissions following the Greenhouse Gas (GHG) Protocol. Developed by the World Resource Institute (WRI) and the World Business Council on Sustainable Development (WBCSD) over a decade-long partnership, the GHG Protocol was published in 2001 and now serves as the basis for nearly every GHG standard in the world. Under the GHG Protocol, emissions are broken down into three (3) scopes.

- Scope 1 – direct emissions from owned or controlled sources, such as onsite fuel combustion for heating & cooling or from campus fleet vehicles

- Scope 2 – indirect emissions from the generation of purchased electricity

- Scope 3 – all other indirect emissions (value chain emissions) such as those from business travel, employee commuting, purchased goods and services, trash disposal, and more

Scope 3 emissions are very hard to capture and calculate fully. Further, it is very hard to benchmark because many organizations will report on only a few different subcategories within Scope 3. However, in the case of buildings, only Scopes 1 and 2 need to be tracked and reduced or offset to claim a building is carbon-free or carbon-neutral.

Reducing energy consumption is the best way to reduce GHG emissions. Not only do efficiency measures minimize utility costs, but they also reduce the number of RECs or offsets that need to be purchased and reduce the size of onsite renewable energy required to cover the building load. Organizations in New York City that make long-term GHG emissions reductions goals can employ various strategies, such as solar storage systems, which can shift over time. Many of these opportunities are described below.

| RECs | Offsets | |

| Unit of measure | Megawatt-hours (MWh) | Metric tons of CO2 or CO2 Equivalent |

| Source | Renewable electricity generators | Projects that avoid or reduce greenhouse gas (GHG emissions to the atmosphere |

| Reporting | Can lower an organization’s gross market-based scope 2 emissions from purchased electricity | Reduce or “offset” an organization’s scope 1, 2 or 3 emissions as a net adjustment |

| Claims | Can claim to use renewable electricity from a low or zero-emissions source | Can claim to have reduced or avoided GHG emissions outside their organization’s operations |

| Purpose | Convey use of renewable electricity generation; underlie renewable electricity use claims; expand consumers’ electricity service choices; and support renewable electricity development | Represent GHG emissions reductions; provide support for emissions reduction activities; and lower costs of GHG emissions mitigation |

Renewable Energy Certificates (RECs)

According to the EPA, “Renewable Energy Certificates (RECs) are the legal instruments used in renewable electricity markets to account for renewable electricity and its attributes, whether it is installed on the organization’s facility or purchased from elsewhere. The owner of a REC has exclusive rights to the attributes of one megawatt-hour (MWh) of renewable electricity and may make unique claims associated with renewable electricity that generated the REC (e.g., using or being supplied with an MWh of renewable electricity, reducing the emissions footprint associated with electricity use). Claims to the attributes of the electricity from a REC can only be made by one party. The purchase or use of renewable energy, verified with RECs, is a decision an organization makes to ensure its electricity is provided from renewable sources that produce low- or zero emissions, thereby reducing its market-based scope 2 emissions.

RECs can be a flexible tool to help achieve clean energy goals, lower scope 2 emissions associated with purchased electricity, and support the renewable energy market.” There are two types of RECs that you can buy: bundled and unbundled RECs. Though RECs (the renewable attributes) and electricity are produced at the same time, the two “products” are severable and represent different revenue streams for project developers. Unbundled RECs represent the purchase of the attributes only and can be matched independantly with electricity consumption.

According to the EPA, “by purchasing RECs and electricity separately, organizations do not need to alter existing power contracts to obtain green power. Additionally, RECs are not limited by geographic boundaries or transmission constraints. For organizations with facilities in multiple states or energy grids, a single, consolidated REC procurement can be part of an organization’s strategy to efficiently meet overall clean energy goals.”

Further, unbundled REC supply has far outpaced demand, driving their cost down, making it a very attractive option. However, while companies can still purchase unbundled RECs to achieve sustainability goals, unbundled RECs do not have as meaningful an environmental impact because they don’t lead to new, “additional” energy being produced and only represent a re-shuffling of the existing renewable energy supply on the market today. In this way, unbundled RECs do not provide “additionality.”

Virtual Power Purchase Agreement

One way to achieve the additionality missing from unbundled REC purchases is through a Virtual Power Purchase Agreement (VPPA). According to Urban Grid Solar, “a Virtual PPA is a contract structure in which a power buyer (or offtaker) agrees to purchase a project’s renewable energy for a pre-agreed price. In this agreement, the utility-scale solar project receives the market price when the energy is sold. If the market price is greater than the fixed VPPA price, the offtaker/buyer gets the difference. If the market price is less than the fixed VPPA price, the offtaker/buyer pays the project to make up the difference.

In this way, a VPPA acts as a financial hedge against volatile electricity prices. Typically, the buyer receives the project’s RECs. Because there is no physical delivery of power, the VPPA is a great option for large electricity consumers with a fragmented/distributed electric load to support the development of new renewable energy resources.”

A VPPA guarantees the project a fixed price for its output, which is critical for developers interested in financing new projects. The energy and bundled RECs obtained through a VPPA are due to a new “additional” renewable energy facility that adds new clean energy to the grid and displaces fossil fuels. The project needs the VPAA to occur, making it truly “additional” and impactful.

Carbon Offsets

According to the EPA, “an offset project is “a specific activity or set of activities intended to reduce GHG emissions, increase the storage of carbon, or enhance GHG removals from the atmosphere.” The project must be deemed additional; according to the EPA, “the resulting emissions reductions must be real, permanent, and verified; and credits (i.e., offsets) issued for verified emissions reductions must be enforceable. The offset may be used to address direct and indirect emissions associated with an organization’s operations (e.g., emissions from a boiler used to heat your organization’s office building). The reduction in GHG emissions from one place can “offset” the emissions taking place somewhere else. Offsets can be purchased by an organization to address its scope 1, 2, and 3 emissions. Offsets can be used in addition to an organization taking actions within its operational boundary to lower emissions. Offsets are often used for meeting voluntary commitments to reduce GHG emissions where it is not feasible to lower an organization’s direct or indirect emissions.

For an organization with a voluntary commitment to reducing its emissions footprint, purchasing and retiring (that is, not re-selling) offsets can be a useful component of an overall voluntary emissions reduction strategy, alongside activities to lower its direct and indirect emissions.”

Examples of carbon offset projects include landfill gas capture, farm animal waste methane capture, abandoned coal mine methane capture, reforestation, and improved forest management.

Combined Approach

Purchasing RECs will offset your global footprint for purchased electricity (kWh consumption). They allow your business to claim 100% renewable status and are, overall, cheaper than carbon offsets. For every 1 MWh (1000 kWh) of electricity generated, one REC is produced. When purchasing RECs, you must evaluate and baseline your electricity load and emissions.

Carbon Offsets can be used to offset Scope 1, 2 and 3 emissions in metric tonnes of carbon dioxide (tCO2e). Using them to offset Scope 1 and 3 emissions allows you to claim 100% renewable status, while offsetting Scope 1, 2, and 3 emissions enables you to claim your business as carbon neutral. To do this, a carbon footprint analysis must first be performed to benchmark Scope 1,2 and 3 emissions.

Electing to purchase a combination of Carbon Offsets (to offset Scope 1 and 3 emissions) and RECs (for Scope 2) will also allow a claim for carbon neutrality.

Purchasing Physical Green Power

Another way to make a strong commitment to sustainability and support the renewable energy industry is by purchasing physical green power.

Onsite Generation

Institutions can install renewable generation assets on campus as a direct power supply, which can have the dual benefit of making the building or campus more resilient by being less reliant on the utility grid. If financing is available for installing and operating a renewable asset, the institution can own it outright. However, there is also the option to enter into a Power Purchase Agreement (PPA) with a third party. The third party will own, operate, and maintain the asset, merely selling back the power to the institution hosting the investment. This kind of PPA is a long-term agreement (often 15-20 years), but it can be structured to include a buy-out provision that allows the institution to become the asset owner at any point before the expiration of the PPA.

Offsite Generation

If for any reason, an institution cannot host the asset at the site where the power will be consumed, PPAs for offsite generation can also be explored. A third party can be brought in to work with developers to find available land or roof space to site the asset. The only restriction is that the renewable asset must be in the same utility grid zone as the consumer.

Notes on Green Power Purchase

When entering these contracts, one must be aware that buying physical green power does not necessarily mean that you can claim it to be zero-emission electricity in many greenhouse gas reporting systems. This is because renewable assets generate two tradeable commodities – first, the kWhs produced, and second, the environmental attributes (RECs) of those kWh.

To formally claim that physical green power is zero-emissions power, RECs associated with the renewable energy generation must be purchased along with the energy and retired from the REC market. However, especially in the northeast, these RECs can be costly, so unbundled RECs can also be purchased instead of those tied to the green power asset. This strategy allows institutions to claim that their power comes from a renewable source and that their electricity consumption has no carbon footprint.

Market Details

REC Pricing

According to Level Ten Energy, “RECs are priced differently depending upon whether they are compliance market RECs or voluntary market RECs. Compliance market RECs are used to meet renewable portfolio standards (RPS), meet certain criteria laid out in the RPS statutes, and are often more expensive. Voluntary REC markets are almost exclusively driven by climate-related sustainability goals, making them more common for corporate clean energy purchasers. Since there are fewer strings attached, voluntary market RECs have lower prices.”

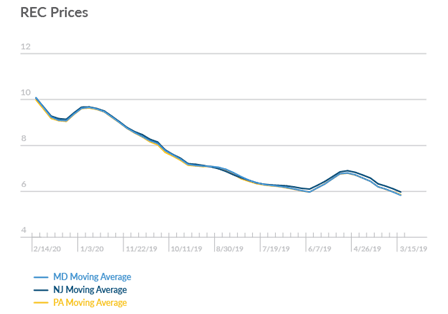

For example, in a recent LSBP survey of institutional broker price sheets, a Vintage 2020 National Green-e certified voluntary REC is currently marked between $0.50 – $1.00/MWh compared to a Vintage 2020 New Jersey Solar REC at $227.50/MWh, a Vintage 2020 Maryland Solar REC at $80.00/MWh and a Vintage 2020 Pennsylvania Solar REC at $40.00/MWh.

Some states even have a tier system for RECs to designate their positive environmental impact, such as Tier 1 RECs coming from new wind and solar projects. These REC prices can fluctuate based on changes to wholesale energy markets. For example, REC prices in Pennsylvania, Maryland, and New Jersey (the PJM grid zone) were expected to increase following the Minimum Offer Price Ruling (MOPR) in December 2019. As a result, monthly moving averages of Tier-1 RECs in those states have been rising from a base of about $6.50 in August 2019 to over $9.50 in January 2020. In contrast, the 2020 Tier-1 REC price for New York State was $22.09. This increased slightly for compliance year 2021 to $22.33/MWh.

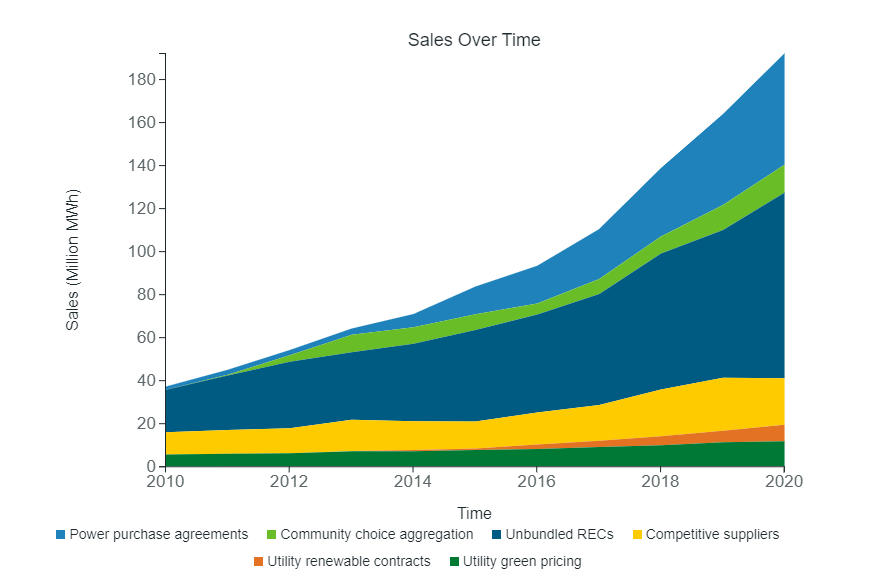

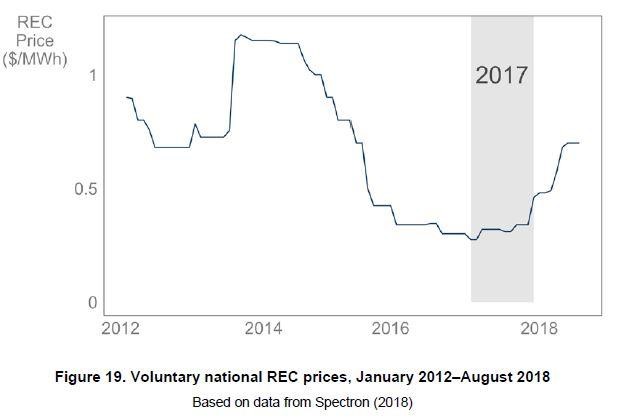

As shown in the above graphic from NREL (National Renewable Energy Laboratory), demand for voluntary unbundled RECs has been increasing greatly. This caused a spike in the market for national Green-e RECs earlier this year, with pricing hitting $6.95/MWh in August. It has since come down to $3.85/MWh, but this still remains much higher than the relatively constant pricing of ~$1/MWh we’ve seen since 2015. This sort of volatility must be considered when deciding whether to achieve sustainability goals through unbundled RECs or a bundled energy + RECs PPA. The below graphic from the EPA shows the voluntary unbundled REC prices from 2014 to 2018

Carbon Offset Pricing

According to Second Nature, “the price of carbon offsets varies widely from <$1 per ton to >$50 per ton. The price depends on the type of carbon offset project, the carbon standard under which it was developed, the location of the offset, the co-benefits associated with the project, and the vintage year. The average offset prices are between roughly $3-$6 per ton.” Large institutions may obtain a lower price per offset for larger volume purchases.

Next Steps

Environ is prepared to help organizations pursue any of the opportunities described. Email info@environenergy.com or fill out our contact form to get in touch with us. Please do not hesitate to reach out with any questions or concerns.

Additional Resources

GHG Standard Programs (set protocols and methodologies, set rules and requirements, processes)

Registries (track credits, assure no double counting):

Validation and Verification Bodies

Sources: EPA.gov, Urban Grid Solar, SecondNature.org, leveltenenergy.com, nyserda.ny.gov, pjm.com